Silo vs. Severance: Twins From Different Mothers

This is part two of my series about the Apple TV+ series Silo and about the books it is adapted from. The first part was about the art and practice of adapting literary works for movies and TV. This part is a look at Silo and another popular Apple TV+ show, Severance. Spoilers abound for seasons one and two of Silo and season one of Severance.

Given a choice between a new book and a new TV show, I’ll usually take the book.

Even in this era of so-call “premium television” — big budget, big stars, big waits between short seasons, I often have to be dragged to the screen. When there were only three networks and PBS, TV was one of the great common experiences in America. Now we don’t have cable or over-the-air television, just streaming services, and it’s easy to miss a show. Or just not have time for it.

I was two seasons late starting Ted Lasso. The friend who convinced me to try it practically bullied me into watching Severance, which I started the day the second season premiered. For a long time I didn’t even know Silo was on, and when I started watching life interrupted about two episodes in, and I had to abandon it for almost a year. I’d already read the books and was prepared to be a fan.

My bully — I mean friend — consumes media at an alarming rate, so much that she forgets what she’s seen. “Oh, I think I saw that a year ago. I don’t really remember it.” Not a great response when I want to discuss something with her. She’s also very opinionated. When I cried “uncle!” and told her I’d watched a couple of episodes of Severance and made some comparisons with Silo, she responded “I read a description of Silo the other day. And shuddered. The opposite of what appeals to me. Post-apocalyptic. Claustrophobic.”

I nearly spat my ramen all over my laptop. At this point, I’d seen the first two episodes of Severance and already had a pretty good sense of the atmosphere, if not the direction of the story. (Since then I’ve finished the first season, and my first impressions at least about the atmosphere of the show are confirmed.) Both shows are solidly in the great traditions of modern science fiction that gave us Nineteen Eighty Four, The X-Files and Pride and Prejudice and Zombies: dystopia, conspiracy theory, and apocalyptic nightmares.

Her impression wasn’t wrong, but what she thought she wouldn’t like about Silo was all over Severance. I took ten minutes from my busy reading schedule and banged out a set of similarities:

Silo: Post-apocalyptic. Claustrophobic (everything happens in a closed world).

Severance: Oppressive. Claustrophobic (everything happens in a closed-off, windowless world or at night, in the rain or overcast).

Silo: People don’t know what is going on in the world around them.

Severance: People don’t know what is going on in the world around them.

Silo: People who don’t conform are sent to their deaths.

Severance: People who don’t conform are punished, though not killed. At least I don’t think they are.

Silo: Resources and behavior are strictly controlled, though most people don’t really realize it. Until they do.

Severance: Behavior is strictly controlled, though most people appear to be okay with it. Until they aren’t.

Silo: Events and forces beyond the knowledge of most of the characters direct their lives.

Severance: Events and forces beyond the knowledge of most of the characters direct their lives.

I found her “claustrophobic” reaction interesting. I am genuinely claustrophobic and have been triggered by watching TV shows (I’m not a fan of televised spelunking), but never by Silo. The silo is huge. The endless fluorescent-lit corridors of Lumon are no less enclosed.

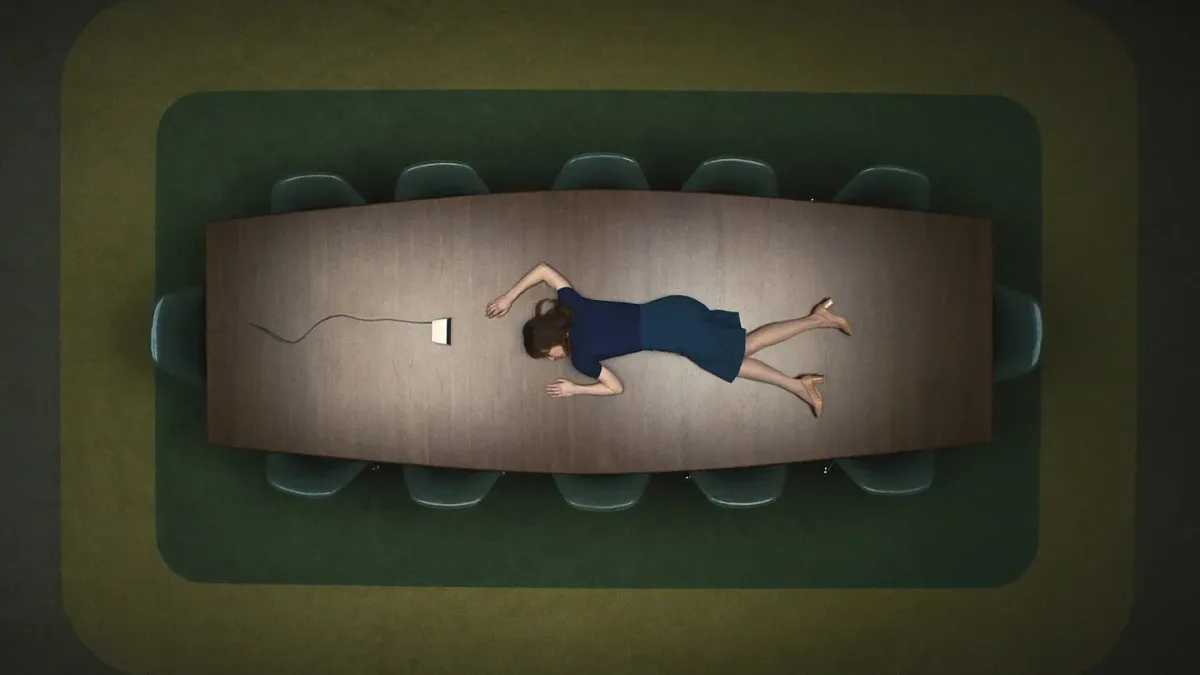

The worlds shown in both shows are very constrained. Silo happens in, well, a silo, the only world its inhabitants have ever known. Severance happens in a brightly lit, almost featureless office where the characters spend their workdays, and most of their time outside the office is spent in darkness or gray, overcast days.

But the psychological restraints are more menacing than the physical constraints. In Silo, people have known no other life. Their whole world consists of 140-plus floors and the 10,000 people who share the silo with them. Silo’s story is how this insular world begins to break free, despite all the safeguards designed to prevent it.

In Severance, being subject to oppression is voluntary, but even so there are darker, hidden forces at work. Though the severed workers know they have separate lives in and outside of office hours, they have no idea what that other life might be like, and it appears in the first season’s final episode this is something Lumon would like to bring to the whole world. Adam Sandler and his team owe a lot to Joss Whedon and his underrated 2009 series Dollhouse, and I hope Dichen Lachman isn’t traumatized by having her character’s personality messed with in two different TV shows.

Both Silo and Severance are stories of the gradual dawning of awareness. The characters in Severance know they have different lives inside and outside Lumon, but innies have no idea of what lies outside their starkly lit offices, and outies have no idea of what their work lives are like. In Silo, the inhabitants are unaware until a few of them sense there’s something more than what they’re being told.

For both shows, unawareness is enforced by oppression, though the characters don’t see it. In Severance, we learn several characters aren’t severed at all and are clearly agents of the oppression — the nature of which becomes clear as the first season reaches its dazzling climax. With Silo, the sources of oppression are as unclear to the viewer as they are to the characters, but the hierarchy of the silo’s society, the culture, and the punishments given to those who don’t meet society’s norms are obviously dictated by someone outside the silo, perhaps someone in the distant past. They live their lives in accordance with a book called the Pact, a code of laws handed down from generation to generation, all culminating in a single, inviolable rule: don’t ask to leave the silo.

The ultimate punishment in the silo is to be sent to “clean.” Cleaning is capital punishment: the perpetrator is dressed in an inadequate survival suit and given a few supplies to clean the lenses of the cameras outside, to give those inside a better view of the bleak world they are told will kill them if they leave the silo. Cleaners live long enough to clean the lenses before succumbing to the deadly atmosphere outside, in full view of the people inside the silo.

The complexities of silo society and culture are well portrayed in both the books and show, but one thing is left out of the first two seasons of the series, and only lightly touched on in the books: religion. Author Hugh Howey is unclear about whether the inhabitants of the silo worship one god or many. But the Pact is the real god of the silo. Though Howey’s brief exploration of religion shows the priests and believers in the worst light, I think the whole population of the silo is a cult, with the Pact as their scripture and the head of IT as its high priest. Only the head of IT and his shadow, or apprentice, have any knowledge of history and what lies outside the silo — knowledge passed down from one head of IT to another, generation after generation. It’s not until the second and third books, and presumably the third and fourth seasons, that we learn what created this situation.

In Severance there’s barely any reference to religion, but Lumon itself is a kind of religion, a cult based on the personality and teachings of Kier Eagen, the company’s founder. There are songs and memorials dedicated to his teachings. Harmony Cobel has a shrine dedicated to him. It’s frightening to think of how susceptible we are to cults of personality, and how it can happen through the culture of a corporation as easily as through a church or other group of people. Severance, at least at the end of season one, shows us how dangerous a cult can be.

I think being late to the party with both of these shows has been to my advantage. When my friend expressed envy that I didn’t have to wait three years between seasons of Severance, I told her “When you’re late there’s no wait.” I’ll be eagerly watching the dance between these two series’ remarkable similarities and differences.